I wrote an article discussing games I thought were almost perfect. Those games were all wonderful, amazing, and perhaps even inspiring in their design, but they had (at least) one fundamental flaw. Today we look at games where, be they wonderful, amazing, inspiring, or even flawed in some ways, managed to utilize one particular mechanic with sheer perfection.

That one mechanic is not going to be improved upon; there is nowhere “up” to go.

Before we start, an example. Many games have used variable player powers over the years. Some have used it well (Twilight Imperium), some have used it with excellence (Small World), and some have just used it (Xia: Legends of a Drift System). Only one has ever used it perfectly (Cosmic Encounter).

Note: the images representing the mechanics are from BoardGameGeek.

Auction / Bidding

Definition: bid on items to improve your standing, always exceed the last bid, and continue until nobody is willing to (or capable of) going higher.

Reiner Knizia’s Ra

Reiner Knizia is amazing, a big deal, creating delightful board games by the hundreds, so he is no stranger to any mechanic. There are 5,173 games listed with the Auction / Bidding mechanic on BoardGameGeek. Some of the best are The Princes of Florence, Power Grid, and Keyflower. No game nails this mechanic quite like Ra.

One of the first things you notice in this auction is that you are limited to a small set of potential bids. The game has 16 numbered bidding tiles. Each player is given a selection of these, plus one is placed in the center of the board. When an auction takes place, the tile in the middle is also being bid upon. When the items are collected, this tile is taken and the tile used to win is placed in the middle. In this way, the restricted bids are constantly changing hands.

Random items are added to the pot with each passing round, but there is a limit to the size. Each time an item is added, it could be a calamity that will force some sacrifice for the one who wins the bid. With each item, a player can call for a round of bidding, or the Sun God may show up and demand an auction happen immediately (or worse, end the round immediately without an auction).

In other words, the auction in Ra is set atop an insane push-your-luck element which drives the content of the pot, the timing of auctions, and the length of the round—all of which results in a mental tug-of-war that puts stressors in all the right places. You know how many potential pots you can capture, but you are not sure of much else (e.g., what will be offered in the next player’s turn, if they will start the bidding, if an auction will be triggered, or if the round will be cut short).

This is auction / bidding perfection.

Closed Drafting (a.k.a. Card Drafting)

Definition: sometimes called select-and-pass. Players are dealt a hand of cards and choose one or more to keep, passing the rest to the next player. Players look at the cards passed to them, repeating the process until all have been distributed.

The Isle of Cats

Frank West has a way of taking the familiar and twisting it just enough to make you wonder if you are truly dealing with the same old idea. Closed drafting is not exactly new in board gaming, having been used in 605 games according to BoardGameGeek, quite successfully in games like 7 Wonders, It’s a Wonderful World, and Terraforming Mars. No game has used this mechanic to better effect than The Isle of Cats.

Things start off normal, with seven cards dealt to each player. Players select two cards to keep and pass the rest. Nothing too odd going on. The cards being drafted are used in several of the later phases of the game.

- Rescue Cats phase: the goal of the game is to rescue cats from the titular island to work into a polyomino puzzle on the player’s ship; this means needing to draft rescue cards to ensure you can attract enough of the right cats to your boat.

- Read Lessons phase: to score the most points requires the completion of private and public goals; this means needing to draft lesson cards to ensure you get the private goals you can complete while restricting what public goals might become available.

- Rare Finds phase: there are not enough resources to rescue enough standard cats to fill the spaces of the boat, so gathering treasures and special cats (Oshax) from the island is important; this means needing to draft rare find cards to ensure you can gather the rare treasure and Oshax cards to fill in the remaining spaces.

Many drafting games include the concept of hate-drafting (drafting items you do not need just to prevent an opponent from getting them). This concept is here, to be sure, but it is significantly mitigated by the fact that after you draft your hand, you need to decide which cards you are going to pay for. Each card has a cost in fish, the same resource you will need to lure cats off the island (each cat needs three or five fish). You get 20 fish each round. In the end, you have seven cards (each costing zero to five fish to be able to use). Hate drafting in this game can bite you in the behind by either costing you fish you need to lure cats, or leaving you with drafted cards you need to discard, limiting options for obtaining cats and treasures.

In the end, a lot of elements are used, pulling you in several directions. This includes resource and hand management, public and private goals, and the ever present polyomino puzzle—which demands luring not just any cats in the market but those specific cats. These elements are deliciously amplified by a draft that has you delicately balancing the needs of several point-gathering elements of the game.

This is closed drafting perfection.

Melding

Note: This mechanic is usually listed as Melding and Splaying. The two elements are distinct. We will consider each half separately.

Definition: cards have relationships allowing some to be played together for greater effect.

Lost Cities

Reiner Knizia is amazing… oops! We already covered that. There are 778 of his games listed on BoardGameGeek as of this writing, so he is no stranger… wait! We already covered that, too. Let’s just dive into this. Melding goes way back, having been used to good effect in games ranging from Canasta (and the whole Rummy family) to Innovation. No game has understood this mechanic better than the two-player Lost Cities.

The game is, from a rules standpoint, simplicity itself. The deck consists of five suits (colors) numbered 2 through 9 along with three cards with a handshake icon (wagers, 12 cards per suit, 60 cards total). The players are dealt a hand of cards. The board has five expeditions, each tied to a suit. On their turn, a player must either play a card on their side of the board aligned with the expedition of that suit, or discard a card onto the board’s expedition space of that suit. Then draw a card, either from the deck or from one of the discard piles (other than the card just discarded, if applicable). That is literally all there is to the game.

Reading that summary, one can be forgiven for not seeing the brilliance of the game. Its genius comes from the restrictions and the scoring system:

- A card must be played or discarded every turn.

- Played cards must be of a larger value than the last card played.

- Handshake cards can only be played if there are no ranked cards in the expedition.

- The score for each expedition with no cards present is zero.

- The score for each expedition with cards present is the sum of the ranked cards present minus 20.

- The score for each expedition is multiplied by the number of wagers placed plus one.

- A bonus of 20 points is awarded for each expedition with eight or more cards present.

- The score for a round is the sum of the scores for each expedition.

- The score for a game is the sum of the scores for three rounds.

Read those bullet points again. Each element in isolation is nothing special, but this is a classic example of being greater than the sum of the parts!

Each expedition, if begun, costs 20 points requiring a total value of 20 in ranked cards just to break even. If wagers are placed and the expedition comes up short, the negative score is doubled, tripled, or quadrupled. When deciding to play or discard, players are often presented with a cornucopia of bad options. For example: starting with a hand of nothing but higher cards, do they start an expedition (risking heavy losses), or discard one (allowing their opponent to draw it)? The choice to place wagers must come early, since they cannot be played in an expedition once a ranked card is there. Each expedition, a melding of cards gathered over the round, is a distillation of the mechanic, which is then elevated by a scoring system that never fails to be beautifully frustrating.

This is melding perfection.

Splaying

Note: This mechanic is usually listed as Melding and Splaying. The two elements are distinct. We will consider each half separately.

Definition: cards have relationships allowing them to be played overlapping one another, revealing characteristics of the new card, or concealing characteristics of a previously played card.

Innovation

If there is a game designer who knows (and loves) the splaying mechanic better than Carl Chudyk, then I am painfully unaware of them. When deciding which of his games to choose for this mechanic, it was truly difficult to decide between this and Glory to Rome. Both are master classes in utilizing a single component (a card) in different ways, depending upon where it is and how it is displayed. Where Glory to Rome has the Multi-Use Cards mechanic down pat (do not be surprised to see it show up in a future volume), it is Innovation that leans into splaying and utilizes it to maximum effect.

Explaining the rules of Innovation is not possible in a short piece. What can be explained is that each card represents an advancement in one of the technological eras of the game. The cards have an icon that identifies them, as well as several other icons indicating the sorts of power and influence the card can provide. Cards have two icons on the left side, which intersect with the three along the bottom. Thus, each card has four icons.

What this means is that a card on top of a stack has four visible icons. When cards are splayed right or up, one icon (the bottom rightmost or the top left icon) of each lower card can be seen. When cards are splayed left, two icons (the left icons) of each lower card can be seen. When cards are splayed down, three icons (the bottom icons) of each lower card can be seen. Add to this the fact that the identifier icon (which has no effect) can be in any of the four locations, reducing the number of powered icons in any of the four directions.

Each of those power icons is important! So many effects in the game are dependent upon who has the most of a given icon, that managing the splay direction, which is only allowed when specific powers on cards are played, can be a bit of a mini-game. Carl Chudyk does not design simple games, but he does design amazing games.

This is splaying perfection.

Prisoner’s Dilemma

Definition: players must choose to cooperate with or betray each other. If both cooperate, they each gain a moderate reward. If both betray, they each incur a moderate penalty. If one cooperates and one betrays, the cooperator incurs a major penalty and the betrayer gains a major reward.

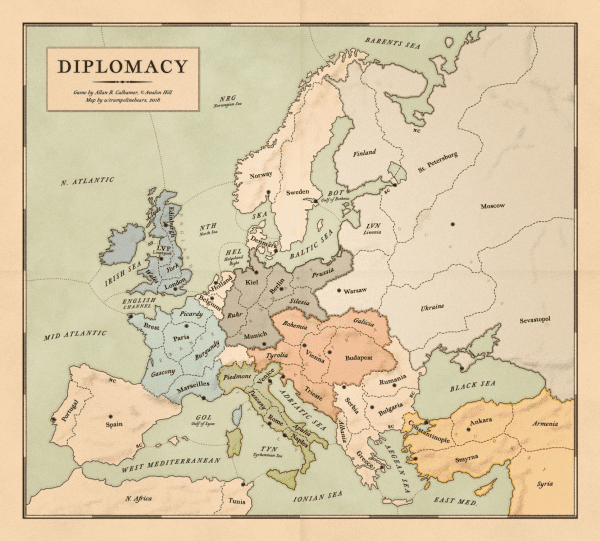

Diplomacy

Diplomacy is not a nice game. To be honest, no game that utilizes—nay, centers its existence upon—the Prisoner’s Dilemma could be. In my review, I warn the reader: this is a game that can (and has) ended life-long friendships, started brawls, and… Well, let’s just say the game is brutal.

The game is a seven player World War I experience. There is a map, two types of pieces (armies and navies), and a balance of the European Powers at the start. Each piece can move one space per turn, attempting to capture supply centers. Two turns plus a reinforcements phase make up a year.

The location of every piece is known to all players. No hidden movement, dice, or special ability cards to muck up your plans. The elements in this game that will muck up your plans are the lies told to you as you negotiate the next move. You see, each turn of Diplomacy starts with negotiation. Players gather in small groups and discuss where this army might attack, or who that navy might support. Each player’s nation is not strong enough on its own to grow, so they need the support of units from other nations. As France works with England to attack a northern German holding, they might also be telling Germany that the plan is to attack a Russian base of operations in Norway, all while Germany is telling Russia that the target is in England… Some of these plans are true. Some are lies. So if the French lose their navy, and the English see Edinburgh captured by Russian forces, it was not an unfortunate roll of the dice, or an ill-timed drawing of the wrong card that caused these calamities. It was Bob and Sue lying to their best friends’ faces while conspiring behind everyone’s back that caused them. And for some, that just won’t do.

This is prisoner’s dilemma perfection.

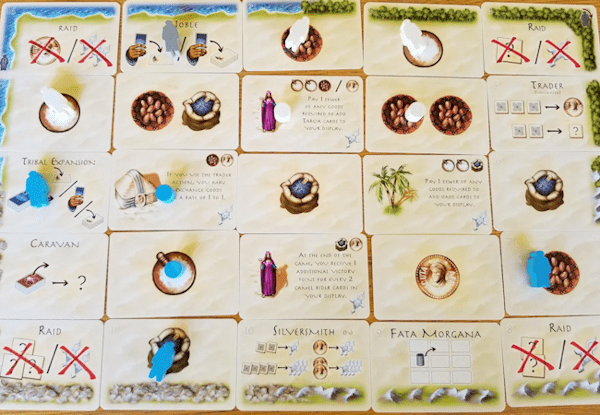

Worker Placement

Definition: multiple actions are available and each player has a number of action tokens (e.g., dice, meeples) to select them. Players take turns placing their tokens, claiming an action. Actions that have been claimed are not (usually) available to others.

Targi

I do not recall when, or with what game, I first experienced worker placement. What I know is that this is an interesting and intriguing mechanic that is popular with several designers and companies. Stonemaier Games, for example, has used this mechanic many times (e.g., Pendulum, Euphoria, Scythe, Viticulture). Three entries for Worker Placement exist on BoardGameGeek (Worker Placement, Worker Placement with Dice, and Worker Placement with Different Worker Types) totalling well over 4,000 games. It is a strong mechanic which has not yet seen the end of the innovation that can come from it. No game captured the essence of this mechanic like two-player Targi.

Targi manages to give the players 21 action spaces and three workers to determine which three, four, or five actions they will take. The board is a 5×5 grid of cards, the outer edge (16 cards) made up of 12 action spaces and four special spaces in the corners. Each worker must be placed on a space along the edge. When all three have been placed, the inner spaces where their workers intersect become the additional actions they can take.

The brilliance of this system is manifold. First, there is the fact that each space can only hold one worker. This is pretty standard in worker placement, but the fact that the opposing space (on the other side of the grid) is also off limits to the opponent is not.

Next, there are the inner nine spaces. These are made up of a random selection of goods cards and tribe cards. Goods cards provide resources, while tribe cards provide special powers and point generating opportunities. The intersection of the workers on the outer edges determine which inner spaces are taken, resulting in the need to use sub-optimal edge spaces to gain access to optimal inner spaces. Each inner space is used once then discarded and replaced with a card of the other type (i.e., goods cards are replaced with tribe cards and vice versa).

Oh yes! I forgot to mention that, along the edge, there is a robber who advances clockwise at the start of each turn. The space he occupies is not available to the workers. When he reaches a corner, he raids the players, stealing resources, points, or gold. Honestly, using a tiny footprint, a plethora of choices, three workers per player generating up to five actions, and an action pool that is in constant flux…

This is worker placement perfection.

Final Thoughts

Six games where each represents perfection in a specific mechanic (IMVHO, YMMV, yadda yadda yadda). Each has flaws, but they are eclipsed by the greatness within. Were I to give each game a full review, none would be rated below four stars. They are great games!

What other games have managed to perfect a mechanic? Meeple Mountain will delve into others in future articles. In the meantime, what games have you played where you noticed a particular mechanic transcending its use elsewhere? Did the rest of the game measure up? Let us know in the comments!

Add Comment