The quality of a game may be objective, but one’s enjoyment of it is not.

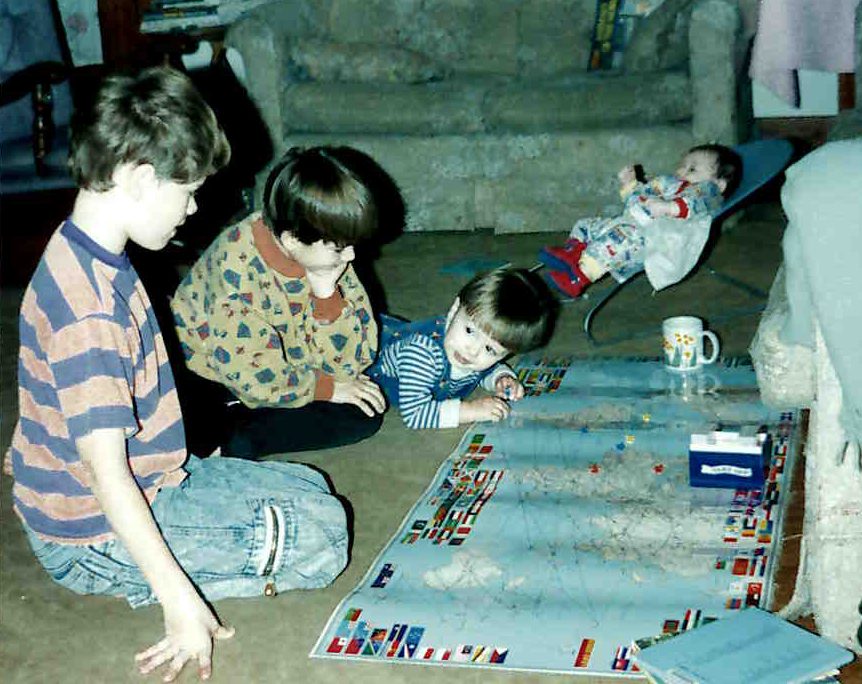

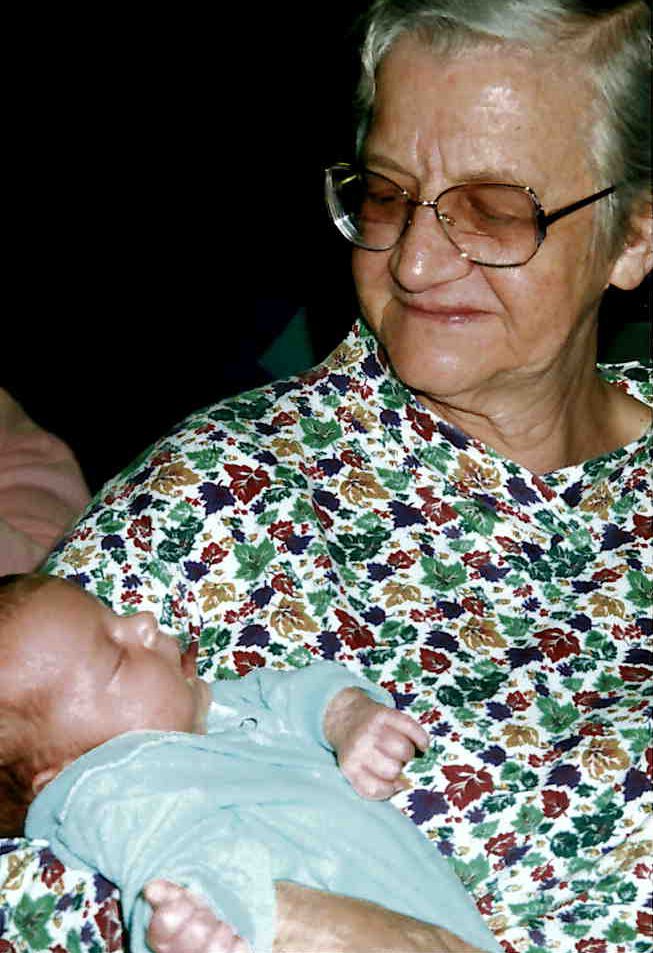

I was never very close to my paternal grandmother. She was a second generation German, a devout woman who was both strict and idiosyncratic in ways that made her hard to be close to. After her husband died and her health began to decline, my father helped her move from Philadelphia out to southeast Minnesota where we lived.

From that point on we saw a lot of her, but the relationship always felt more dutiful than anything else. She was a constant presence at family holidays, gatherings, and even just weekly visits. Here was a woman some 65 years my senior who still showed the signs of growing up in the depression-era, a woman who believed straight-laced and well-groomed equalled good and moral and intelligent. To 10-year-old ragamuffin me she may as well have been from another planet.

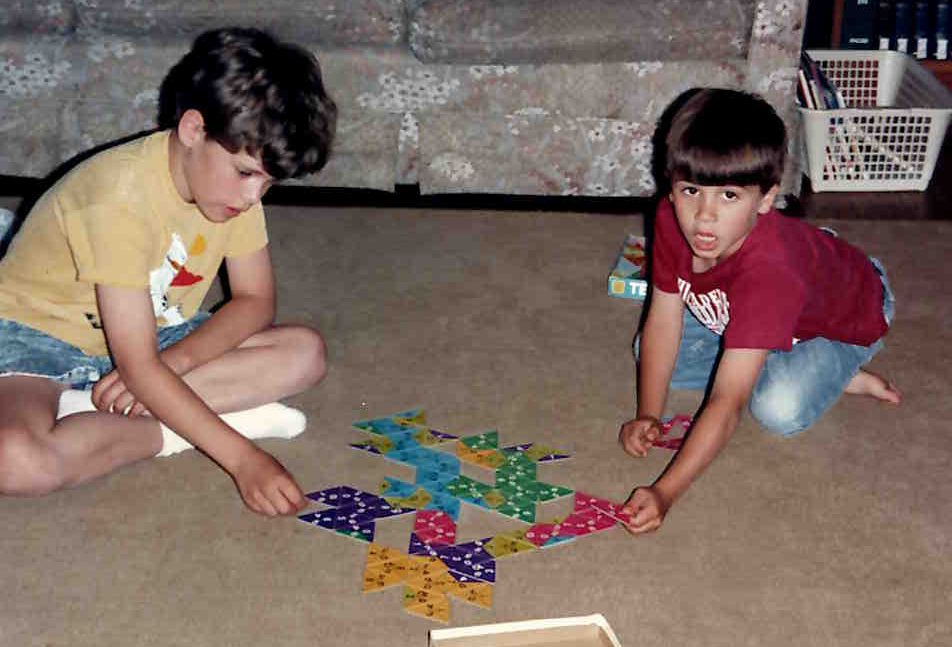

I obediently hugged her at every visit, counting the seconds until I was free to race back to my bedroom and my bucket of G.I. Joes, Battle Beasts, and Dino Riders. That is, until I realized something: she was the one person in my family who, due to her geographical distance up to that point, would still play board games with me.

From the time my cousin taught me checkers when I was about 5-years-old, I had taken quickly and energetically to games, very rapidly burning through the already-short list of family members who would play anything with me. I was fiercely competitive and an abysmally poor loser, a combination which meant that after a few years no amount of pestering or cajoling would get my mother or older brother to play anything with me.

Enter Freda Giannini, whose German stubbornness made an uncanny match for my German-Italian precociousness. It was something — really the only thing — that we found ourselves able to connect over (and in retrospect it was all effort on her part to meet me on my young, selfish terms.)

We quickly found that chess was too complex for her, and checkers too mundane for me. And then, by necessity, we found a happy medium in Monopoly (one of the 5 games that made up my family game cupboard at that time). It wasn’t hard, and Grandma Freda could mostly get by rolling dice, moving her piece, and then deciding if she wanted to buy or not. And for me it offered the opportunity to try and be cutthroat, buying up every land I could like a prepubescent real estate tycoon.

I’m not sure if we ever actually finished a game, as things would typically devolve as I got more aggressive and she got more confused until finally one or both of us would quit out of frustration. That didn’t stop me, however, from begging her to get out the Monopoly board each and every time she visited from there on out, and in the years before she died we played countless times: me, always the pewter dog, and her not caring what piece she had.

I don’t know when the last time we played was. At a certain point I grew up and moved away, and not long after that her health declined further until she passed away. By that time I had changed considerably, as had my taste in board games. I was still some years away from being fully immersed in the hobby, but I had progressed to the point of playing Pandemic, Betrayal at House on the Hill, and Carcassonne. It had been years since I’d played Monopoly, the last time undoubtedly being with Freda at some family gathering I’ve now forgotten.

I’ll be the first to say that Monopoly is a bad game. Your moves are telegraphed and yet randomly assigned by the dice, with your only meaningful decisions being to buy or not, and the wise answer is always to buy, leaving you with really no choices at all. It’s not a game that is currently in my collection, and it’s not a game that I will likely play with my own children if and when I have any. It is, however, a game that I love.

Much like the guilty pleasure of Rocky IV or the indulgence of a Big Mac, Monopoly holds a cherished place in my heart not based on its own virtues but more on my own associations. It conjures up images of my childhood home, my entire family under one roof, and of an inscrutable grandmother who I otherwise had very little relationship with.

I won’t go so far as to claim that I feel personally attacked by the constant, vitriolic rhetoric that surrounds Monopoly within the boardgame community anytime it’s as much as mentioned, but I will offer this: love of a thing comes in all shapes and sizes, and it doesn’t always have anything to do with the quality of the thing itself.

Nicely written! BTW, the game in the first picture is “Tens”.

Thank you the kind words, and for the ID of Tens. I’ve updated the piece!