Introduction

Napoleon famously said, “An Army marches on its stomach.” Some attribute this saying to Frederick the Great. Whoever said it, logistics — that is maintaining an armed force’s supply lines while disrupting those of the enemy — is essential to winning wars. So how do today’s wargames model logistics, if at all?

A very good argument can be made that logistics won the Second World War. The Axis powers didn’t have enough logistics. The Allies had it coming out of their ears. The same can be said for the Punic Wars, the U.S. Civil War, and the Great War. The Roman Republic, the Union and the Entente Powers, respectively, had more resources available to them which ultimately affected the outcome of those wars.

I’ve been playing wargames for over 40 years and to be honest I’ve never really considered the implications of logistics until recently. The company I work for is developing tools that allow the military to more accurately model logistics in professional wargames, which started me thinking about how logistics is modeled in hobby wargames and how that impacts game play.

Tactical, Operational and Strategic Level Logistics

For example, logistics was paramount to the success of Operation Overlord — the invasion of France in 1944. Once Allied troops landed and established a beachhead, it was the Allies’ ability to build up their forces and supplies faster than the Germans that eventually led to the breakout and dash to the Rhine. The Allies invested heavily in logistics to make Overlord successful by using floating harbors (the famous Mulberries), executing Operation PLUTO that laid oil pipelines under the English Channel between England and France, investing in air and sealift assets, and so forth. The plan also included measures to degrade the enemy’s logistics, such as the Transportation Plan for the strategic bombing of bridges, rail centers, and marshaling yards and repair shops in France. All these measures focused on logistics and gave the Allies a decisive material advantage.

At the strategic level, logistics is arguably even more important. A case in point was the Battle of the Atlantic during World War II. Knowing that Great Britain relied on imports from its overseas possessions to feed and sustain its population, the Kriegsmarine employed commerce raiders like the Graf Spee “pocket” battleship and U-boats to stop the flow of food, ammunition, oil and other supplies to England. In response, the Allies invested heavily in escort ships, radar, sonar, longer range aircraft, escort carriers and other anti-submarine warfare technologies to protect their convoys. The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest running campaign of WWII, without whose victory the Allies could not have won the war.

It is at the operational and strategic level that logistics can affect the outcome of a wargame. Thus, wargames at these levels should try to model logistics in a way that is historically realistic yet doesn’t make the game unplayable.

How Operational Level Wargames Model Logistics

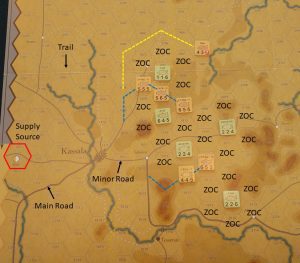

One commonly used concept in operational level wargames to account for logistics is the line of supply, or LOS. In the example shown below from Compass Game’s Forgotten Legions, each combat unit must be able to trace a LOS from its location to a supply source. The game rules allow the unit to trace an overland LOS of a specified length (6 hexes) from the unit’s location to a road or rail line, which in turn can be followed back to a supply source (shown here in the red hexagon). Both the overland and road portions must be free of enemy units and their zones of control (ZOC) as these would block the LOS. The dashed blue lines indicate the valid LOS for each of the British units. Note that a friendly unit negates an enemy ZOC in the hex it occupies, thus allowing most of the British units to trace a LOS. The yellow dashed line shows that the British mechanized unit cannot quite reach the supply road around the Italian units. While it could reach the British 5-5-5 unit, the road leading directly out of that hex to the south is in an enemy ZOC. Therefore it is out of supply.

If the LOS is blocked, then the unit usually suffers some negative effect, such as a reduction in combat strength or elimination if the LOS cannot be restored. Consequently, when playing wargames that use this method, a player must be careful how units are positioned to ensure they are in supply and cannot easily be cut off from an ultimate source of supply. Conversely, your opponent is looking for ways to cut off your units’ supply so they can be more easily defeated.

While this is a very simple method to implement that doesn’t bog the game down in a lot of minutiae, what it fails to consider is whether there is an adequate flow of “bombs, beans, and bullets” moving along the LOS. They also assume there are enough transportation assets —trucks and rolling stock — to move the supplies from the source to the combat units on the front line. Of course, these assumptions are just that — assumptions.

For example, during the German invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa), the Wehrmacht often suffered from a lack of supplies. Hitler’s refusal to fully mobilize the German economy until late in the war meant there were insufficient trucks and transport aircraft available to haul the necessary tonnage to the forward areas. Even though the Germans confiscated hundreds of trucks from occupied territories, these vehicles were not able to withstand the rigors of Russia’s largely unpaved road network and broke down. Even moving supplies by rail proved difficult because the Germans had to first convert the wider Soviet rail gauge to the narrower European gauge. The end result was that the further the Wehrmacht penetrated into the Soviet Union, the weaker they became.

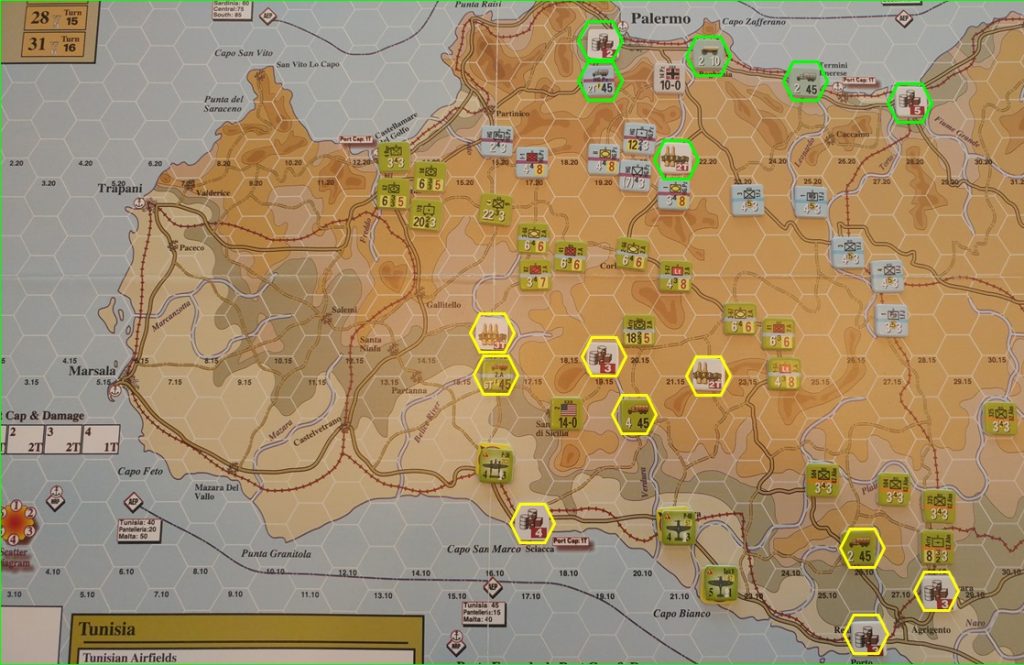

One game system does try to capture some of these factors. The Operational Combat Series (OCS for short) from Multi-Man Publishing makes logistics a game within a game. Each side has a fixed number of transportation assets (trucks, horse-drawn carts, etc.) which they can use to move supplies up to the front. Shown here from Sicily II are the German supply depots and transportation assets in green, and the American supply depots and transportation assets in yellow. The supplies themselves come in two flavors, ammunition and fuel. All units need ammunition, but only mechanized and motorized units need fuel. Without it, they are completely immobilized.

This is exactly what occurred in 1944 when the Allied armies began running into fuel shortages on the Western Front as their supply lines stretched hundreds of miles from Normandy to the German frontier. Until ports closer to Germany could be captured (notably Antwerp), the Allies had to rely on the Red Ball Express truck convoy system to move oil from the Normandy ports to the front line.

OCS games are not for the faint of heart; the rules clock in at nearly 60 pages. However, if you can get past that, the game can be very rewarding as it favors the player who can think in the long-term and make plans accordingly. I suggest starting with Reluctant Enemies, which covers the British and Free French offensive into Vichy-controlled Lebanon and Syria (Operation Exporter), as it is the “simplest” game in the OCS series. Once the basic concepts are grasped, players will begin to better appreciate the role of logistics.

Another innovative mechanic used for modeling logistics is Ted Racier’s chit pull system in The Dark Valley by GMT Games. Many games use the chit pull system as a means of creating the “fog of war.” Rather than one side moving and attacking with all their units before the other player can do the same, in a chit pull game you randomly draw a chit from a cup that represents a combat formation (division, corps, army, etc.). All units belonging to that formation within command range of that formation’s headquarters can then move and attack. This not only introduces uncertainty, but it also keeps both players more engaged since you do not have to sit on your hands while the other player takes their turn.

What makes The Dark Valley somewhat unique is that the mix of chits available to the German and Soviet players change from turn to turn, as shown here on the Action Chit Availability Chart. What this recreates is the inexorable strategic deterioration of German forces and their logistics infrastructure resulting from the Allied bombing campaign and other factors as the war progressed, and the corresponding increase in Russian arms and equipment as the factories they moved beyond the Ural Mountains began producing. The way this affects the game is exactly how it did in real life. The German player needs to strike hard and deep early in the game to achieve their victory objectives before the tide of logistics reverses course and they are faced with the Soviet juggernaut.

Other operational level wargames use different systems to simulate the effect of logistics. In Avalon Hill’s The Longest Day, both sides are provided with supply markers that are consumed by headquarters if they activate two or more subordinate units. The number of supply units available to each, which not only represent fuel and ammunition but also the vehicles needed to transport them, varies with the Allies receiving much more than the Germans. This means the Germans will fight a largely defensive campaign with a small number of counterattacks from their more powerful panzer formations. The Allies, on the other hand, will have sufficient supplies to attack almost every turn at key points along the front lines, but not everywhere.

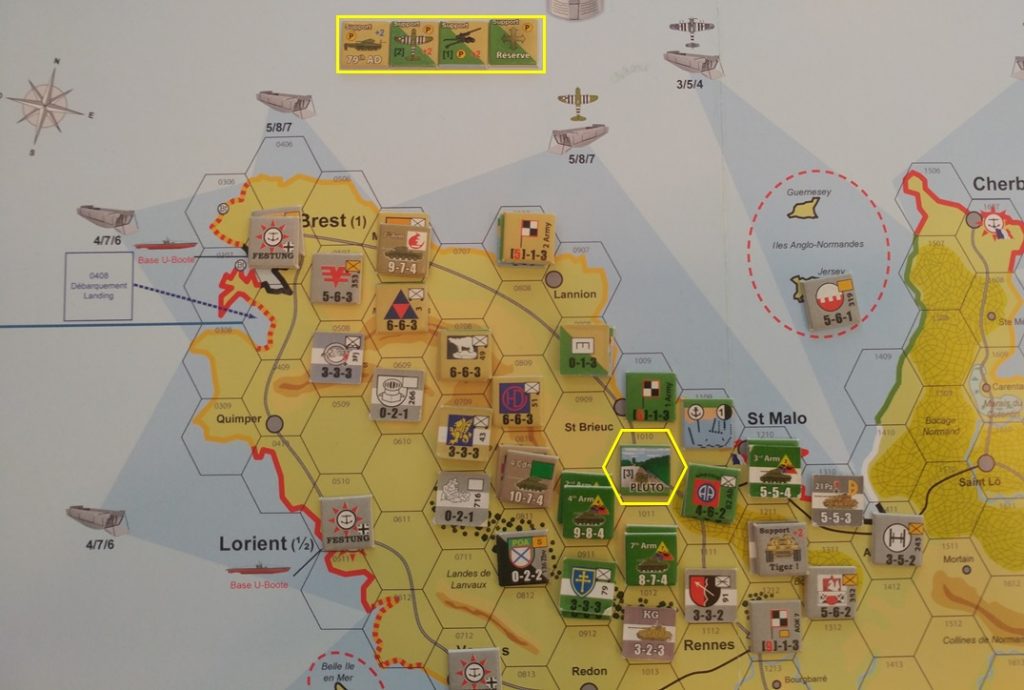

The PLUTO marker in Hexasim’s Liberty Roads performs a similar function by limiting the Allied ability to use support markers — which represent aircraft, artillery, and other assets — across the entire front. As seen here, the Allies have placed the PLUTO marker in the American sector. The four available support markers — the armor, artillery, air and reserve support markers — can only be placed within three hexes of the PLUTO marker. That means the British units pushing towards Brest are on their own.

As you can see, the systems vary from the simple LOS mechanic to the detailed supply system in OCS games. The LOS mechanic is the least invasive (short of totally ignoring logistics), but as we noted earlier, it does ignore important facets of logistics. At the other end of the spectrum, OCS’s more realistic logistics and supply rules make the game more complex and difficult to learn. But regardless of the system, they all affect how the players approach the game.

How Strategic Level Wargames Model Logistics

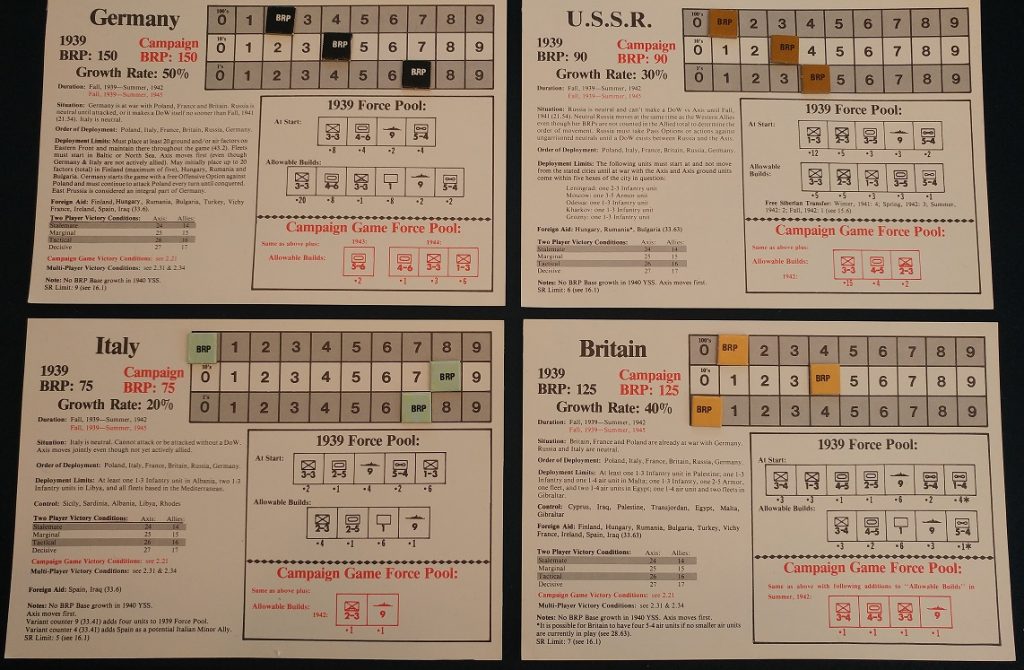

Strategic level wargames model entire wars or theaters of war. Therefore, their portrayal of logistics is more abstracted than in operational level wargames. One of the first strategic level wargames was Rise and Decline of the Third Reich by Avalon Hill. Each nation starts the game with a specified number of Basic Resource Points (BRPs) which represent the economic potential of that country. BRPs can be used to declare war, conduct offensives and build new units. Each country also has a BRP growth rate that simulates that nation’s ability to grow their economy. BRPs can also be gained by conquering other nations or be reduced as a result of strategic warfare and loss of territory. The number of BRPs available to each nation is kept track of on player aid cards as shown here. For example, Germany currently possesses 247 BRPS, while Britain has only 140. Wisely managing the use of BRPs is the key aspect of the game. This kind of system does require some bookkeeping but is generally not too onerous.

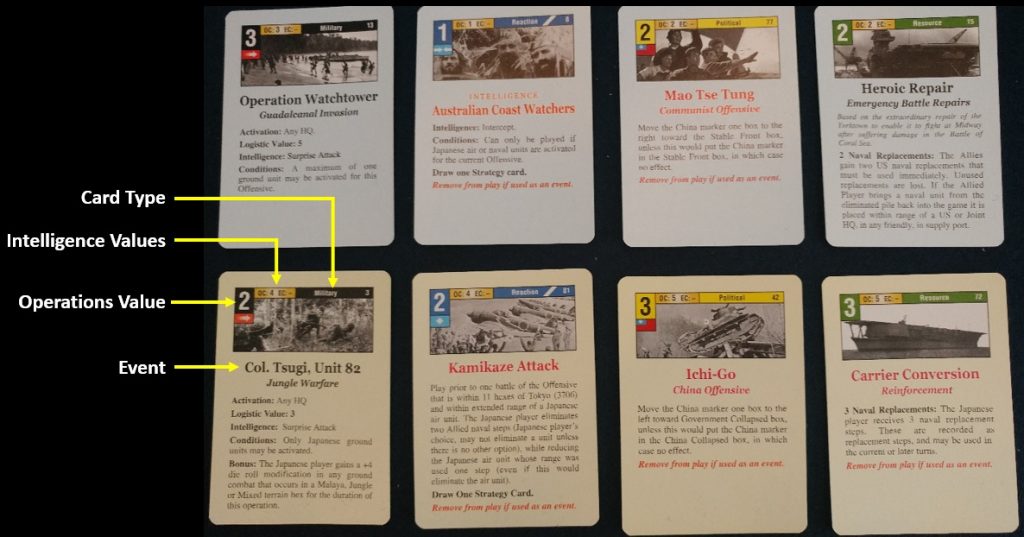

Another system used in strategic level wargames to model logistics is in card-driven games such as GMT Games’ The Napoleonic Wars, Paths of Glory, and Empire of the Sun. The economic and logistical capabilities of the combatants is determined by the number and type of cards they have available each turn. As with most card-driven wargames, each card can be used for the event printed on the card or for the value printed on the card. The value of the card can be used to conduct operations, place control markers, build new units or other activities. Shown here are some sample cards from Empire of the Sun.

The card’s value represents resources in much the same way as the BRPs in Rise and Decline of the Third Reich. The players must judiciously use their cards and the resources they represent to maximum effect. This kind of system is simpler since no bookkeeping is involved. By regulating the numbers of cards and what cards are available to each player as the game progresses, it is possible to simulate the ebb and flow of economics and logistics for each nation.

Victory Games’ Pacific War designed by the venerable Mark Herman uses a simple and somewhat unique method to model logistics. For the larger campaign and strategic scenarios, each player bids a number of Command Points (CPs) from those they have available each turn. While bidding is a mechanic seen in many other types or board games, it is extremely rare to see it in a wargame. The player who bids more is the Action player and can use the CPs they’ve bid to conduct offensives. The loser is the Reaction player.

In the example shown here, the Japanese have conquered French Indochina and Malaya and are poised to attack the Dutch East Indies next. If the South Headquarters in French Indochina wants to activate the units shown in the inserts, it must spend 22 CPs (the sum of each unit’s activation cost shown in red on the counter). Because the number of Activation Points is greater than 20, but no more than 30, this is considered a Level 2 operation. As such, the South Headquarters must pay twice it’s operation cost of 4. That brings the total to 30 CPs that must be spent for a 14-day operation. If the Japanese want to activate the units for 21-days, they must pay twice that much (60 CPs), and three times as much (90 CPs) if they activate for 28-days.

Early in the war, the Japanese player receives more CPs to reflect Japan’s higher level of readiness, mobilization and stockpiling of resources before the Allied embargo. Later in the war, Allied industrial potential outpaces the Japanese, especially as the Allies retake territories and resources conquered by the Japanese. The more units each headquarters activates, and the longer they are activated, the more CPs will be consumed. This prevents players from being able to act or react with as many units they might wish, which is exactly what modeling logistics is supposed to do. As such, both players will spend a considerable amount of time at the beginning of each turn deciding how best to allocate their CPs to launch offensive operations or react to enemy moves. GMT Games is releasing a second edition of Pacific War later this year.

Other strategic level wargames use entirely different systems for modeling logistics. What they all have in common is trying to represent the changing economic and industrial output of the belligerents and the impact that had on their ability to sustain combat operations.

Conclusions

Should wargames model logistics? I think the answer is yes. Simple “fairy dusting” of logistics wherein opponents have unlimited resources at their disposal does not accurately reflect the real world. Even when one side in a conflict had more resources than their opponent, they still had limits on what they could accomplish with those resources. Wargames should not only be entertaining; they should also be instructive and try to simulate the kind of difficult decisions faced by all commanders. Let’s hope designers continue to develop innovative, but not overly complex, ways to model logistics in wargames.

Really cool article! Thanks. It is good to see that Meeple Mountain is not ignoring the heavier components of the gaming hobby; wargames were a part of my experience in gaming for many, many years. Not so much these days (different group of people to play with these days).

Although I am unlikely to delve into the games you bring up in this analysis, I appreciate the coverage and the information presented.

Thank you. I’m glad you enjoyed the article.

Excellent analysis.