Whether born in a flash of genius or cultivated over seasons, many great game ideas never make it to the table. Why? Oddly, the creative process cracks open the door for doubt and fear. Agonizing over foolish questions like “Is the idea good enough?” or “Am I skilled enough to pull this off?” can undercut the joy of game design.

But when excitement overpowers dread, creative expression is possible! Today we are going to shut the door on doubt and fear so we can focus our creative process on quickly converting that spark of an idea into a playable prototype. Let’s make a game!

Define the Core Experience

Take your spark of an idea and, before you apply mechanisms or start “designing,” think about people playing your future, completed game. What do you want them to feel? How many are there? How do they interact with each other? How long should the game take to play? Defining the core experience is a grounding process that can allow the spark to announce what it wants to be.

For example, let’s assume we are designing a game about Tennis. Is this a thinky, 2-hour Euro game or a brief filler-style experience? I am thinking we design a light, family style game, two players competing head to head, where the interactions are shot-by-shot, back-and-forth rising tensions of watching a thrilling rally in just one point of a tennis match. In fact, let’s say it’s the most important point – “Match Point.” There, the game just told me its working title! Thanks, Spark!

Now write down the core experience. Novels of notes are not helpful at this stage. Your concept should fit on the back of a napkin. This simplicity will preserve that spark of genius, even though the design will fundamentally evolve later on.

Choose a Constraint

Limiting your design choices may seem counterintuitive, but creativity needs structure the same way a car needs a road. Constraints can be by component (design with no dice, all dice, only 18 cards maximum, language-independent cards with only icons, etc.), player count, game duration, and so many more. Try different constraints of your own choosing and see how your design reshapes itself.

In our tennis game “Match Point,” we constrain ourselves to a single point in a match, the purest melee combat expression of sport. We imagine playing cards (or dice) for unique “strokes” like Lob or Volley. The design is taking shape. But modeling only the last point of the match might not be enough “game” to satisfy players. And thematically it places one player always near victory and the other player desperately trying to stave off defeat. But only one player has clear victory conditions. Thinking it over, we switch to the set tiebreaker, where both players start at 0 and must be the first to reach 7 points (and win by 2) to achieve victory.

Most important at this stage, don’t censor your ideas. Give the design permission to flop until it aligns with the core experience. New constraints will force you to reconsider earlier assumptions. Some constraints will not work at all. Thank them for their time and shove them in the drawer. We cannot be bothered by missteps – we are designing!

Sketch the Rules

As broadly as possible, on the back of an envelope or a Post-It note, rough out the rules you feel are “solid” (e.g., turn order, action selection). Then, and most importantly, jot down thematic player interactions that evoke your core experience. This sketch is only for you (and you will quickly throw it away) so limit yourself to about five minutes of jotting.

“Match Point” seems to encourage players to choose shot types in response to their opponent’s shots. We assume there will be a finite amount of “cards” (or dice, still not sure!) representing the player’s stamina during the point. We make a note about special shots – Overhead Smash, Serves – and vow to revisit those after we have figured out how to make basic ground strokes work. Shot selection also suggests that location on the court matters, which brings to mind a board with minis, but now we are straying from the core experience, so let’s pull it back, add it to the list, and work just on ground strokes for now.

Assemble an Ugly Prototype

Think of how far we’ve come! We know how many players, what the core interaction feels like, and we’ve shaped that experience with a thematic constraint. We even have scribble-scratch rules! Now it’s time to play-test. “But wait,” you might think, “the game isn’t finished yet.” No, it’s not. By testing each design assumption by itself, we can isolate what is not working and try to correct (or discard) it.

So, why must the prototype be “ugly”? In short, the less attractive it is, the less emotional investment you have, which prevents any one design choice from crowding out better ideas. If we now spend 15 hours building beautiful cards, it is harder to dump cards in favor of dice. We may try to save the cards (and the work that went into them) even if they no longer support the core experience.

Pull together bits from other games – cards, dice, checkerboards, index cards, poker chips, markers & pencils, Post-Its, whatever you like. Use these as stand-ins for fully developed components.

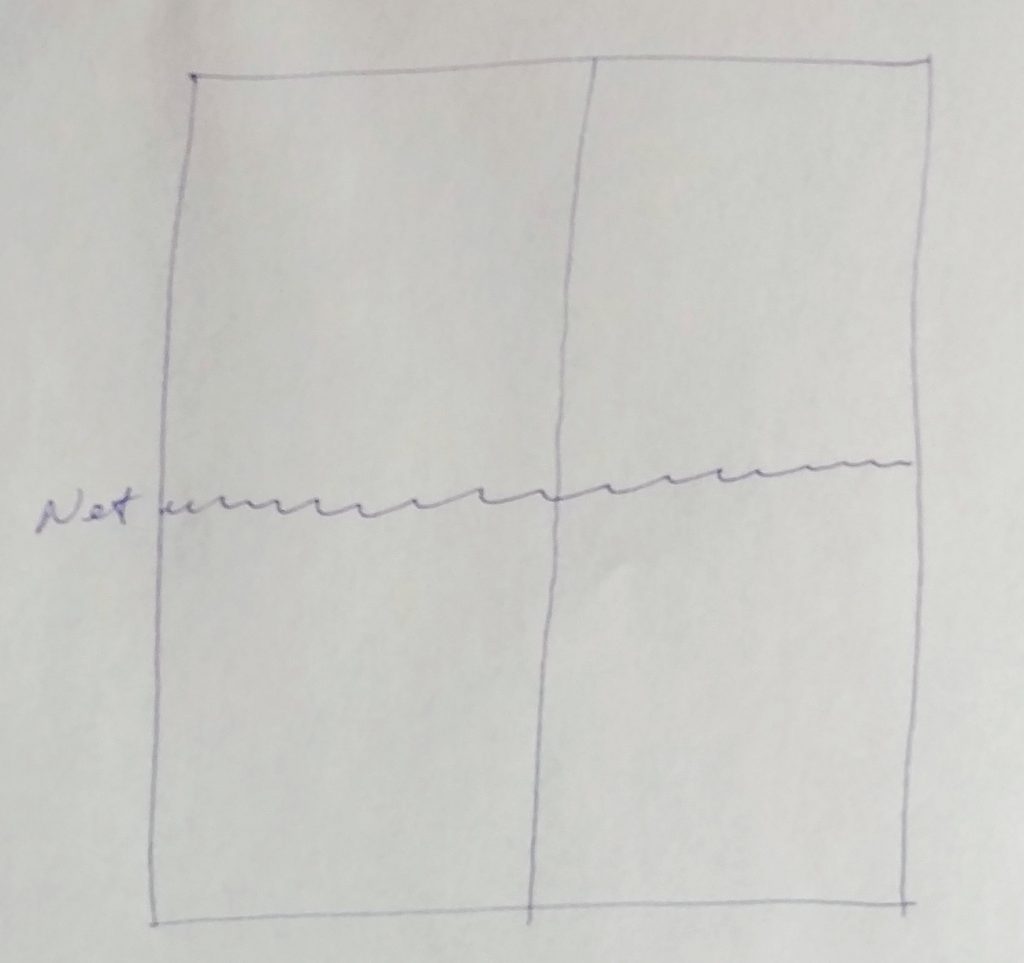

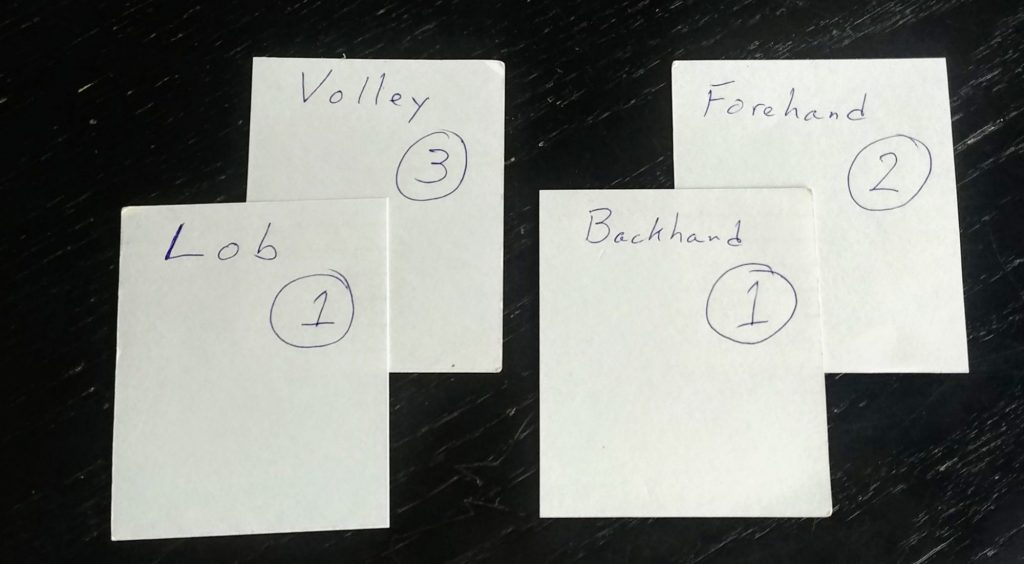

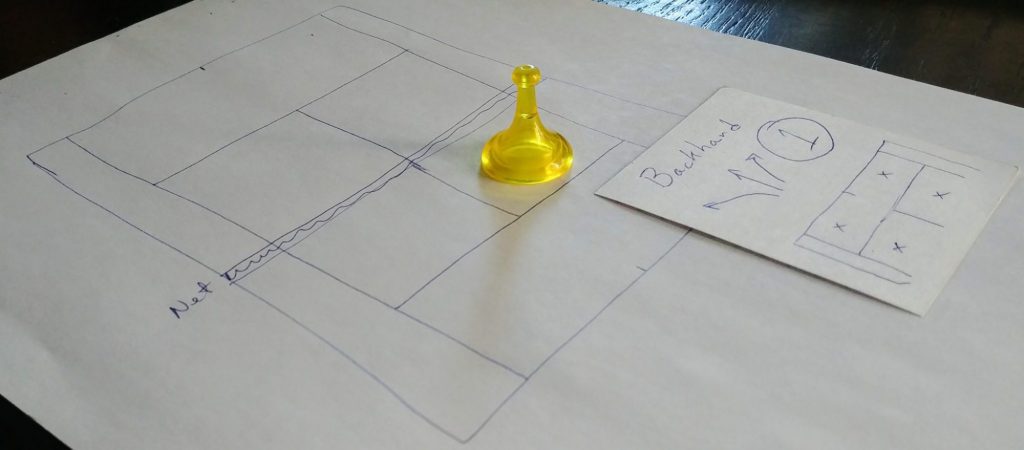

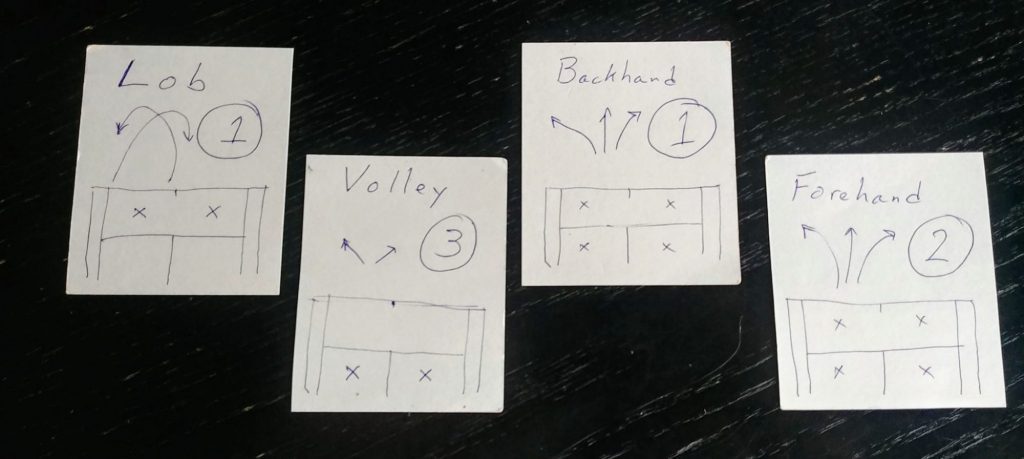

For “Match Point,” we choose index cards with one-word shot titles (Lob, Volley, Forehand, Backhand, etc.) and a single digit power rating. We draw a tennis court on a sheet of printer paper, four quadrants with a net in the center, to serve as our playing surface.

Test One Element

In these early stages, you can’t test enough. These are simple tests, like opening a door to check the hinge. Do it solo at first and be amazed at how simply pushing pieces around the table spotlights obvious improvements. You will find it pleasant, even liberating, to discard concepts that don’t work and downright delightful to uncover the ones that do.

When we put “Match Point” on the table, index cards with a paper court, we quickly recognize we need to track where the ball is on the court. Head smack. Shake it off. We get a pawn from Sorry to mark the ball. Now whenever we play a card to hit the ball, we need to move the pawn to our opponent’s side of the court.

Update Rules & Improve Ease of Play

Every time you make a decision, update your rough rules document. Avoid the temptation to start codifying rules, doing layout, selecting artwork. That is development work, and there is plenty of time for that later. Once you outgrow the napkin, move to a dedicated notebook or Word document. When you iterate frequently, it is critical to maintain your “official” working rules.

Components must ultimately help players. As you get deeper into the design, add the information needed to play the game. Aesthetics are not important, but is the most important information easy to read? Is some info now duplicated or unnecessary? Are player aids needed to track information? Make your changes quickly so you can get your prototype back to the table.

Testing “Match Point” suggests lateral direction arrows are needed on shot cards so players can work their opponent side-to-side on the court. These are sketched on the index cards and included in the running rules document, which is now almost a full page of notes in Word.

Once the design does not break in testing, you can pivot to developing aesthetic components with placeholder artwork.

Lather. Rinse. Repeat.

“So when is my prototype done?” Simple…never. Remember, the prototype is not the game. The prototype is the thing you make and destroy repeatedly until your game design aligns with your core experience. Development creates the components. But design creates the experience.

Look back at our process. We took the spark to a functional prototype about halfway through this article. The moment we put bits on a table to test the core experience, we had a prototype. All we needed was a spark of a game idea and the relentless willpower to work at it.

As you deepen your game design skills, stay true to your spark’s core experience and conquer designer’s block with this mantra: “The game is not the bits. The game is the experience.”