Crowdfunding has altered the way many products get to market.

Kickstarter has helped products come to fruition in a wide variety of areas: from comic books to software; from fashion to music (be that concerts or independent albums). It is the go to method of funding for many. More than 250,000 projects have been funded on Kickstarter, with almost $8 billion (with a ‘B’) from over 90 million pledges.

Statistically, tabletop games make up the single largest segment of Kickstarter projects, both in terms of revenue and number of funded campaigns. This market is so large that Gamefound, another crowdfunding platform, was created to handle nothing but this class of product. They boast almost 1,500 projects, over €400 million (over $430 million) in pledges from a million backers. Add in Backerkit, and one can see that crowdfunding and tabletop gaming are working hand-in-hand.

Whole companies have gotten started because of crowdfunding. Stonemaier Games began with a Kickstarter for Viticulture. Stonemaier’s co-founder has written many blog posts detailing how to run a successful crowdfunding campaign; he eventually wrote a book on the topic that is considered by many to be the gold-standard. Crowdfunding can be a great thing! It has given voice to many who did not have the ability to bring their ideas to the world otherwise.

Rake in the Money + Deliver Nothing = Scam?

As I said, crowdfunding has altered the way many products get to market. For some of us who frequent these platforms, backing projects sets us up to be emotionally invested; sadly not every crowdfunding story is a happy one. Many campaigns have surpassed the funding goal and delivered nothing. Very often this is accompanied by creators ghosting their backers. A simple internet search yields a shocking number of crowdfunding campaigns that, to some, appear to have been scams. I have talked with many people who have been burned by crowdfunding campaigns; some have sworn off the idea using these platforms in the future.

I have not reached that point. Yet.

Disclosure: I ran a campaign on Kickstarter for Arcanum 30th Anniversary Edition, a role-playing game from the 1980s for which I had purchased the rights. I met my funding goal, but everything went sideways. I was not going to be able to deliver the books. I stopped, scrimped and saved, got enough money together, and refunded everyone 100% of all pledges. A few years later, I ran another campaign for that same book, met my funding goal, and delivered on my promise. This is not to say I am better than anyone. It is to inform you, the reader, of my experience on the other side of this. That said, I cannot imagine being able to do this if my campaign had been an order of magnitude larger and things had fallen through.

I have backed a lot of crowdfunding campaigns; I fully support this grass-roots method of getting an idea out there. I have contributed to campaigns that never delivered, and several that continue to push delivery dates out further and further. Are these scams? I have no way of knowing, really. It does appear that some project creators abuse the generosity of their backers.

I have backed nine campaigns where what I was supposed to receive never came. Those campaigns have resulted in:

- $210 – refunded by apologetic creators: it’s disappointing, but the backers were made whole. These were probably not scams.

- $400 – lost to creators who ghosted their backers: it’s infuriating, but there is little the backers can do at this point. Some of these could be scams; others could just be a collection of unforeseen events.

- $832 – locked in campaigns being updated years after their promised delivery date: it’s frustrating to be told story after story as to why the backers have to wait another month or quarter or year. It leaves a lot of people not knowing how to feel about things. Will the backers ever get their product? If so, when? These may or may not be scams; at what point can one say either way?

That last group is very difficult to judge. Consider the Kickstarter campaign for Republishing the World of Synnibarr role-playing game. The campaign was supposed to be delivered in late 2013. In 2014, the creator reported that the books were ready to print; then nothing. Some felt the creator had ghosted them. Then, in July of 2022, an update declared that everything was completed. By all accounts, it appears that the creator completed the project and got the product into the hands of the backers… some eight or nine years late.

So what is the solution?

The solution, if there is one, will depend greatly on where the responsibility should lie. This is not something that everyone agrees upon. The three entities where responsibility can be placed are:

- The backer

- The platform

- The creator

The Backer

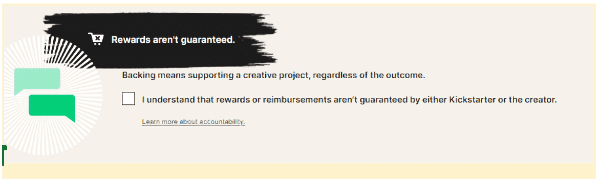

Right now, the responsibility lies with the backer. If nothing is done, the responsibility will continue to lie with the backer. This is because crowdfunding is not a purchase, it is an investment. The backer gives money with the expectation they will receive something, that the creator makes something, and so on. That expectation is not a guarantee. Much like any other form of investment, things can result in a loss, breaking even, or profit. But if things do not go the way the backer wants, that was the risk taken.

The Platform

Right now, best I can tell, the most Kickstarter is willing to do is to warn backers that this is not a purchase. Kickstarter has a page dedicated to explaining there is no guarantee and they are not responsible when it comes to the promises made by the creators. Their job is to provide a “safe and reliable” platform. Nothing else. It is the backer’s responsibility to vet the creator; it is the creator’s responsibility to fulfill their promises. Full stop.

Gamefound has a page which explains that it is not a store. That said, a campaign can put a limitation on itself by joining the Stable Pledge program. Under certain very specific circumstances, backers of campaigns utilizing this limitation can get a full refund. These conditions however involve a change in the price structure, not a lack of fulfillment.

The question is: what would it look like if the platform could be held partially or fully responsible for unfulfilled campaigns? It would mean a lot of additional infrastructure. Ebay has the eBay Money Back Guarantee. I have no idea what this costs eBay each year, but this is as close to how one could hold Kickstarter fully responsible for the delivery of pledged items as it gets. The problem is that projects on crowdfunding platforms are not extant products; they have to be manufactured. The risks a platform would incur would be cost prohibitive. Even a partial refund on a project could be huge.

For example: the Frosthaven campaign raised $13 million. Suppose this campaign had not been fulfilled; how much should the platform be responsible for? If the amount is less than 100%, would the backers be happy? Would this drain on the platform be sustainable if more than one project fails in this way? Should the platform be responsible for something over which it had no control?

The Creator

For some, if there is a right place to assign some or all of the responsibility, it would be the creator. They made a promise; they did not make good on that promise. What does that look like?

It appears that the closest applicable law to handle this sort of thing is fraud (I am not a lawyer and I do not play one on TV). What constitutes fraud in these cases? How do you enforce it? Would this mean backers need lawyers in order to sue the creator? One suspects they could do this already, so why don’t they? Could it be because the cost of the lawyer is prohibitive? Could it be because proving their case might be very difficult? How would you prove that fraud took place and not incompetence?

Should the platform be involved? On which side would they belong? No matter which side they are on, the other will feel as though the platform does not care about them. Either way, they risk losing creators and/or backers. It is a lose/lose situation for them.

Final Thoughts

I have backed 150 projects; 115 were successful; 35 failed in some way, shape, or form. Above, I describe how nine of these campaigns are either never going to reach fulfillment, or will be several years late; two refunded my money. I have had at least decent results with 94% of the funded campaigns I have backed. Talking with others, this is fairly typical.

Do some people run fraudulent campaigns? Yes. The best advice I can give is to know who you are backing. Look into them; find out what sort of track record they have. Oh! And never put more in that you can afford to lose.

Do we need consumer protections with crowdfunding? No (IMVHO, YMMV, yadda yadda yadda).

I say that with some bitterness. I want there to be consumer protections! The projects where I have supported the creator, and the project was abandoned before anything came of it left me feeling empty. But the problem, as explained above, is in where to assign liability.

- If we hold the creator liable in any way that would result in their need to refund all or part of the funds to the backers, then crowdfunding dies. At what point does a campaign cross the line from bad luck or incompetence to outright fraud? If any failed attempt to reach for the stars can be met with legal action, no creator is going to take the risk.

- If we hold the platform liable in any way that would result in their need to refund all or part of the funds to the backers, then crowdfunding dies. Where does the platform get the funds to refund the backers? Would this just be a cost of doing business? If a platform is held responsible for the actions of people over whom it has no control, no platform is going to take the risk.

This means that if crowdfunding is to continue – and I truly want it to continue – then the responsibility must remain with the backer. Consumer protections cannot work within the crowdfunding framework.

I know how bleak this sounds. Early in one of those failed projects above, I was exchanging emails with the creator. I was running my first attempt at Arcanum and we were talking about what we wanted to accomplish. I thought we had become friends. Then his campaign imploded; being ghosted hurt. I not only lost $200, I lost a friend. Was the campaign a scam? I have no idea; I hope not. In my heart, I try very hard to give them the benefit of the doubt.

There is an argument that can be made for adding consumer protections in crowdfunding, but this argument ignores the realities of the framework. Backing a project is not purchasing a good. It is an investment in the creator. If everything works out, you will get what you hoped for. But this is not a guarantee.

There are most certainly people who have used these platforms as a way to con people out of their money. But how can you know? There currently exists no mechanism by which we can look into the heart of a person and know their intentions. So in the meantime, the best advice remains caveat emptor – buyer beware.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about a very relevant topic, as I imagine many (if not all) the readers of your article likely have had at least one negative experience with a crowdfunding project. There are a couple of points I would ask you to consider that were not addressed in your article.

All three parties bear responsibility, but not equally, especially because the process of vetting a creator is the most problematic for the backer. Other than a history of previously launched campaigns and their binary outcomes (delivered vs. unfilled), how does the average backer vet a creator’s experience with communication skills, contracting various manufacturing processes, establishing effective distribution partners and their ability to manage the uncertainty with a stressed global freight system? There is no database that I am aware that offers any kind of relevant, granular data that could be a useful proxy for rating the creator’s ability to deliver their project. The platform itself seems best capable to collate this historical data, and while it would require investment to provide such a database, this information seems important enough that the dissemination could be monetized in some way to offset the cost of maintenance. The platform itself could create a system of “pre-verification” that would provide some assurances that the creator appears capable of bringing the proposed project to fulfillment (perhaps a list of engaged manufacturers, distribution & freight agents and copies of contracts with each), with such status requiring an additional fee from the creator.

I would also caution about the presumed clear demarcation between purchase and investment. In general, most platforms do offer appropriate reminders that there is no guarantee when the backer supports a project, but this message may not be as effective when well-established companies continue to launch multimillion dollar campaigns that many view as pre-orders. After receiving their 10% fee, the platforms have every incentive to firewall themselves from any liability related to unforeseen production or delivery issues. There’s very little the average backer can do to protest either the established creator or the platform when communication becomes infrequent or delivery targets are grossly missed.

Do I think consumer protection agencies would solve these issues? Not entirely, but there is a growing body of legal actions by various state AG’s that may shape the liability environment around crowdfunding. When KS announced in 2021 its desire to use blockchain technology to make a “decentralized crowdfunding protocol”, a number of high-profile creators abandoned the site due to concerns about the environment impact of the power consumption required to administer such a system as well as the potential for fraud.

Buyer beware is good advice in any age, but that assumes that the backer has some current knowledge about the market conditions driving changes for creators and platforms alike, and the possible avenues of abuse for which the backer will be left holding the bag.

I just read your comment, and I have to say that all of this is very well thought out. Thank you, Mr. Romanelli, for your thoughts and questions. The main thrust of you comment is, as I am sure you are aware, far more than I am going to be able to pull from my brain instantly, and would require more space than is appropriate here in this comment.

That said, I will delve into what you are saying and asking, and I will get you an answer as soon as I can. And when I do, I will find a way to answer you in a medium and manner best suited.

Again, thank you. This is some wonderful stuff to mull over.

Hi! I have reached out to a local law office that deals in fraud. I hope to hear back from them soon. Assuming I can get an interview and delve a little deeper into this topic, I will write up a new article as a follow-up to this one.

Thank you for your interest, and your questions!