A version of this article first appeared on The Sciku Project.

Watercolour feast

Self-contained ecosystem

Suddenly too hot

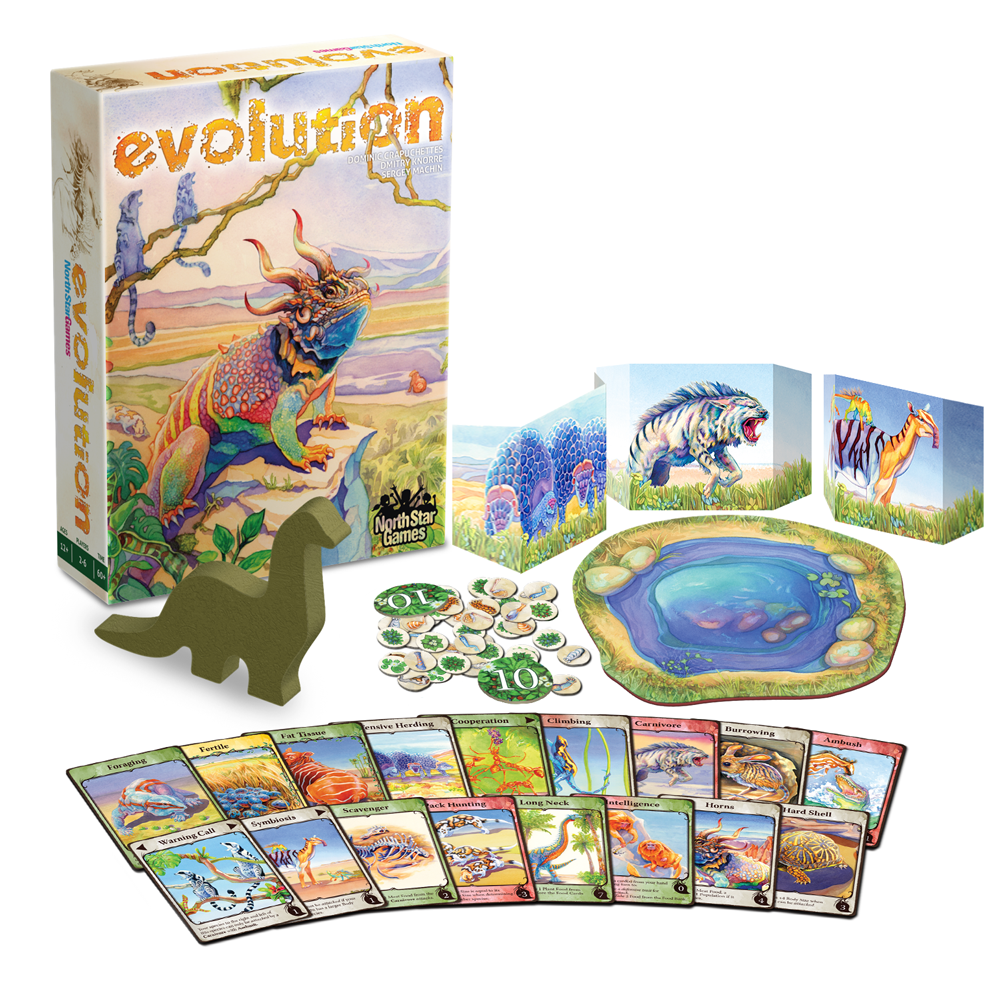

Recently I decided to combine two of my passions – science communication through the medium of haiku and writing about board games – to create a collection of board game haiku. The haiku that leads this article is taken from that collection and is about a board game called Evolution: Climate, designed by Dominic Crapuchettes, Dmitry Knorre and Sergey Machin. As the title suggests, the game focuses on the theory of evolution and the impacts of climate on species survival.

In the game each player controls a number of species (generally 1-3) and ‘evolves’ those species to meet the needs of the game environment based on the current climate, the availability of food, and the other species competing for that food. The player whose various species have eaten the most food over the course of the game wins.

What makes Evolution: Climate interesting as a game are the various traits your species can evolve and the way they all interact. Some are straightforward: ‘Foraging’ lets a species take an extra food token from the central supply; ‘Long Neck’ allows a species to access the food supply first; ‘Heavy Fur’ and ‘Mud Wallowing’ enable a species to survive cooler or hotter temperatures.

Other traits are more complex, allowing players to create intelligent symbionts that feed and protect one another. Oh yes, I said protect. The game includes carnivorous, defensive and scavenging traits that turn a mild herbivorous experience into an arms race where species can, and will, go extinct due to hunger or predation.

Whilst this all sounds like it might be complicated, it’s surprisingly streamlined and approachable, in part because of the science it’s based on. The concept of evolution and the survival of the fittest are such well-known ideas that most people are able to grasp the game without too much trouble. But, famous though it is, the theory of evolution is also one of the most misunderstood concepts in science and researchers can spend a lot of time trying to make their subject clear for the general public.

So is Evolution: Climate science communication? Can board games even be forms of science communication?

What is Science Communication?

There are a number of definitions of science communication, but most involve something along the lines of “communicating science-related topics to non-experts” (definition from the British Interactive Group Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Communicators Network). I rather like Wikipedia’s definition: “the practice of informing, educating, sharing wonderment, and raising awareness of science-related topics”. “Sharing wonderment” feels like it should be the unofficial motto of my site ‘The Sciku Project’.

Science communication takes place for a variety of reasons. We can benefit from an improved understanding of our existence – scientific knowledge can help us navigate an increasingly complex and technological world. Science communication can influence political decision making (for example around policy issues of health care or animal welfare) and plays a key role when it comes to popular misconceptions about cutting-edge science (think of the refuted idea that the MMR vaccine causes autism).

Better public awareness of science can also lead to greater numbers of students choosing to continue down STEM career paths, leading to global economic benefits and further advancements in every aspect of our lives. There are other economic considerations too. Research is often funded through taxpayers’ money. Morally, it’s important that scientists share their findings, justifying how the funding was used and what the results were (this also means that, for researchers, effective science communication can be a route to accessing further funding).

What’s interesting about science communication is how it’s changed over time. The traditional concept is largely one-way: an expert telling non-experts something about their subject. But as the limitations of this approach have become more apparent there has been a movement towards two-way communication.

Dr Sam Illingworth, Senior Lecturer in Science Communication at The University of Western Australia and co-director of the Manchester Game Studies Network, has one of the clearest definitions of science communication: “communication between scientists and non-scientific publics”. Note that communication is with not directed at, and the term ‘public’ includes a whole range of people with very different experiences, educations, interests and needs. It’s why science communicators are continually exploring different mediums for communication, including board games.

Board Games as ‘Accidental Education’

Educational board games are not new. In 1903, Elizabeth Magie created The Landlord’s Game, which served to illustrate the negative aspects of concentrating land ownership in the hands of a privileged few. Today, the game is known as Monopoly. Similarly, The Game of Life dates back to 1860 with the release of The Checkered Game of Life by Milton Bradley, who designed the game to have a moral message (that people should be continually vigilant against the vices of humanity and the world).

Following a crash in popularity in the 1990s, board games have seen an enormous resurgence over the past decade, with the industry predicted to be worth an estimated $12 billion by 2023. The reasons are many – improved game designs, increased production quality, the need for human interaction and social bonding, a rejection of screens and the digital, not to mention a global pandemic that has resulted in millions of people staying at home and looking for new ways to be entertained.

With the tabletop resurgence has come a whole raft of new games designed to educate as well as entertain. Some use STEM-concepts and history as a background against which to design a game. Looney Labs have a range of science-themed editions of their hugely successful card game Fluxx, a game that has you playing cards that change the rules and even how you win as you go along. It’s silly, quick and easy but designer Andy Looney worked with scientists to ensure that the Anatomy, Astronomy, Chemistry, Math(s) and Nature versions of Fluxx contain a wealth of accurate information about their subjects. These games present scientific concepts without asking the players to necessarily engage with them, operating a form of information osmosis without getting in the way of the fun.

Chemistry Fluxx and its siblings are just one of a variety of games that use scientific ideas as a background for exciting gameplay. One such game is 2019’s critically acclaimed Wingspan, in which players try to place birds into their natural habitats in optimal combinations, with the game’s cards crammed full of information about the different species of birds. Wingspan’s designer, Elizabeth Hargrave, calls these types of games “accidentally educational” – games that teach the players about their subject without appearing to be instructive. Keeping to the natural world, Hargrave’s follow up, Mariposas, has players guiding monarch butterflies in their annual migration around North America. Other games that use STEM-ideas include:

- Photosynthesis – a game of cultivating trees to convert the most sunlight into energy.

- CO2: Second Chance – a cooperative game where players represent energy companies trying to keep carbon dioxide levels down around the globe.

- Terraforming Mars – a game that has players juggling oxygen levels, temperature and the creation of habitats in preparation for the colonisation of Mars.

Board Games as Science Communication

Whilst some games use science as a background, others are designed from the ground up to educate. Genius Games specialises in such games, although the term ‘educational game’ tends to be avoided as it conjures up ideas of dull games that preach but don’t entertain. John Coveyou, a former chemistry and physics teacher, set up Genius Games to create “great games designed accurately around hard science concepts”. Coveyou has designed games that have players activating organelles inside a human cell (Cytosis: A Cell Biology Game), collecting elements from the periodic table (Periodic: A Game of the Elements), and building atoms using quarks, photons, protons, neutrons and electrons (Subatomic: An Atom Building Game).

These are games that dive deep into the science of their themes but never neglect the point that board games are meant to be fun. You don’t need to know anything about the science behind the games in advance of playing but may find you know a little more at the end of the game. Intentionally educational without requiring players to do any of the pedagogical heavy lifting.

Nerd Words: Science!, another game from Genius Games, asks a little more from its players. Participants are divided into 2-3 teams, with a player tasked with giving one-word clues and the teams trying to work out the scientific term the clues are about. For instance, the term might be photosynthesis and clues could be sunlight, plants or oxygen. Whilst many of the games I’ve covered don’t require any prior knowledge of the subject, in Nerd Words: Science! players need to have some understanding of the science terms in order to creatively think of and interpret the single-word clues.

Taking an even more proactive approach to educational board games, some designers are using funds to boost charitable work or inspire players to make a change in their lives. Endangered has players trying to convince UN Ambassadors to save vulnerable species (tigers and sea otters in the base game) whilst simultaneously trying to keep those species surviving long enough to be saved. The team behind Endangered worked with the Centre for Biological Diversity during the development of the game, created a ‘tip jar’ that allowed backers on Kickstarter to donate to the Centre, and have worked to get copies of the game sent to schools, libraries, museums, zoos, and aquariums.

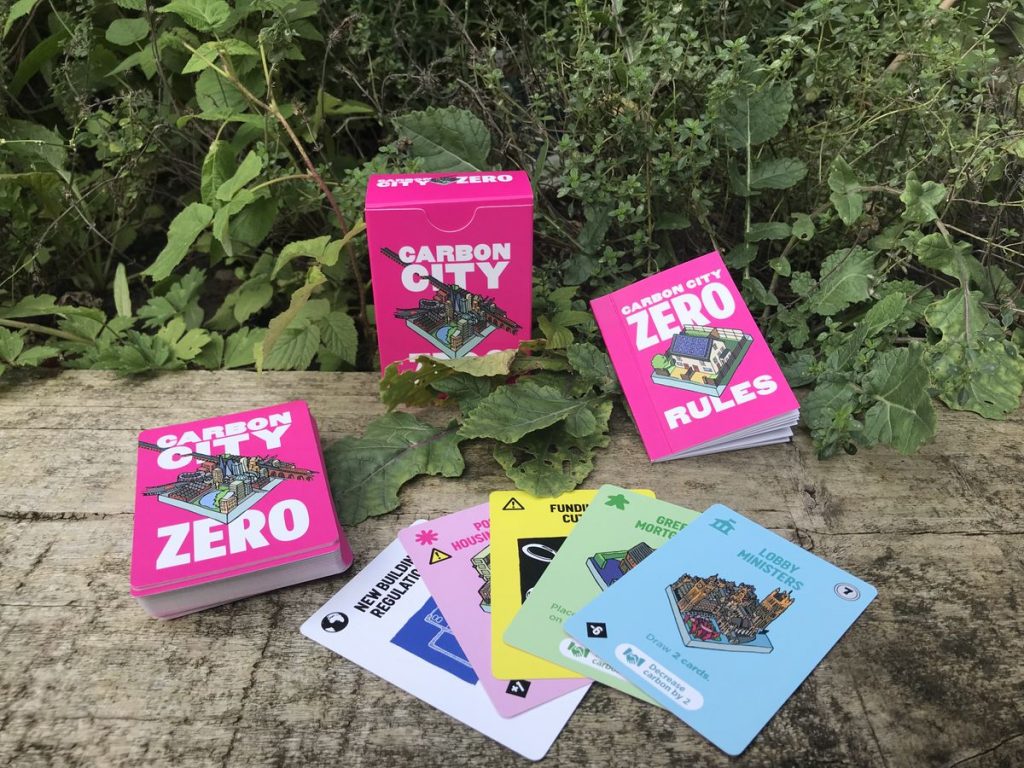

Similarly, Carbon City Zero is a game created by researchers at Manchester Metropolitan University and specifically designed to get the players “talking about cleaning up our energy system”. The game is a race to create a carbon neutral city and involves concepts such as fuel poverty, green mortgages, public awareness and governmental lobbying. The team (which includes Dr Sam Illingworth, of the nice science communication definition) has worked hard to ensure that the production of Carbon City Zero doesn’t have a negative impact on the environment either – it’s “fully reusable, replayable and recyclable”.

Profits from Carbon City Zero are being used to produce additional copies of the game to distribute to schools and community organisations across the UK, free of charge. The second, updated edition, Carbon City Zero: World Edition, has recently been successfully funded on Kickstarter and you can check out a great overview by the always excellent Dr Michael Heron (Senior Lecturer in Interaction Design in Games and Graphics at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden) on his website Meeple Like Us.

Finding the Evidence

But are any of these games actually doing what their designers intended? Are these board games effectively communicating science? Well, away from the anecdotal there are an increasing number of studies emerging that look at how board games can affect knowledge, communication and behaviour. For instance, Fjællingsdal & Klöckner (2020) have shown how games such as Catan: Oil Springs, Evolution: Climate, Global Warming, and Keep Cool can be used to generate environmental awareness:

“Being able to visualize and experience environmental issues within the safe confines of the game is a unique way to immerse learners into the subject of environmental literacy, and might even represent a possible solution to the problem of environmental issues being perceived as non-salient”.

Catan’s availability and approachability make it a good framework for science communication. Whilst it wasn’t created as a tool for education, the Catan: Oil Springs scenario has been shown to “influence people’s awareness about sustainability issues and affect people’s behaviour regarding sustainability issues” (Chappin, Bijvoet & Oei, 2017). A later study specifically designed an additional scenario (Catan: Global Warming) and found that the game resulted in “dialogue around global warming both at and away from the table” (Illingworth & Wake, 2019).

Whilst it is still a burgeoning research area, it’s clear that tabletop games can and are being used as effective tools for science communication, helping to create meaningful two-way dialogues between scientists and non-scientific publics, making science “more accessible, and more informed, by the many publics that exist in our society”. No area of science seems to be off limits, from the microscopic Subatomic to the interstellar scale of Planetarium, which has players creating planets in the embryonic universe.

Survival of the Fittest

By far the most popular area of science for board games, though, is biology, and specifically evolution. In the last decade the tabletop hobby has seen simple games that take Darwin’s theory as a rough theme for a fun experience (Darwinning! and Darwin’s Choice) to the complex Dominant Species that recreates the struggle for existence between taxa as the last ice age was just starting.

Board games have also delved into the history of the scientific study of evolution. Players can retrace Darwin’s famous voyage in On The Origin of Species, discovering new species and the links between them. Those more interested in genetics can temporarily inhabit Gregor Mendel’s shoes and get into the nitty gritty of pea plant cross-breeding with the fascinating Genotype: A Mendelian Genetics Game (a game that genuinely features Punnett Squares as a central mechanism).

So let’s come back to Evolution: Climate, the precursor of which, Evolution, was purposefully designed by Russian biologist Dmitry Knorre to “demonstrate evolutionary principles to his students”. Is Evolution: Climate an effective tool for science communication? What does it actually teach us about the theory of evolution? This last point is an important question because the concept of players overseeing the game and choosing traits for species so that they’ll survive carries with it the dangerous whiff of intelligent design.

Whilst I have a Masters and a PhD in Evolutionary Biology, all those really signify is having had some luck, persistence and time in my twenties. Let us instead turn to someone far wiser than I – Stuart West, Professor of Evolution at the University of Oxford. In his review of Evolution published in Nature West said that the game “features sophisticated biology… captures key aspects of the evolutionary process and would work as a teaching aid for ages ten and up”, and could “help older students tackle specific topics, such as evolutionary arms races”. In fact, West was so enamoured with the original Evolution that he’s listed as a scientific advisor in the credits of Evolution: Climate, along with paleoclimatologist Dr Giles Young, health data scientist Dr Joanne Demmler, and artist and scientist Catherine Hamilton, who was also responsible for the gorgeous artwork of the game.

I agree with West. Quite apart from being beautiful to look at and great fun to play, Evolution: Climate does an effective job at communicating an idea about evolution that is surprisingly difficult to understand. With up to 6 players and potentially 20 species, the nuances of how different species interact and react to one another comes through as one of the strongest elements of the game. The species created and their specialised traits depend upon all the other species currently in play and the climate at the time. Individual players can set up chains of their own species that act as self-contained ecosystems, a delicate arrangement that can be utterly disrupted by the arrival of a large predator from across the table.

What Evolution: Climate provides is less an idea of genetic inheritance and change through random mutation, and more the external forces that shape which traits persist and which die out. It’s an aspect of the subject that’s frequently misunderstood; it’s hard to comprehend the sheer number of factors that affect a species’ survival over extended periods of time. Evolution: Climate does a fantastic job of simulating this, whilst providing an entertaining and, at times, ruthlessly competitive game.

Yes, as players you get to choose the traits that appear and influence the climate within the game – the determined could latch onto the idea of divine guidance and claim intelligent design. But that trace of pseudoscience is only there if you’ve never played the game, never experienced the shifting environment as species appear and disappear and the climate fluctuates. After your first game of Evolution: Climate you’ll realise that evolution isn’t just about the traits that appear but how those traits cause their species to thrive in their habitat… or not. Your understanding of this aspect of evolution is fundamentally changed through the simulated microworld that the players create and influence.

I think that nicely answers the question of board games being effective science communication tools.

Add Comment